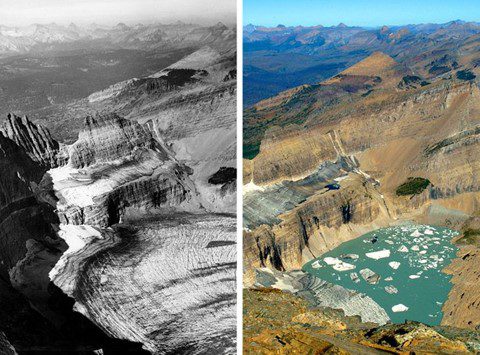

A recent Stanford study found that climate change caused one-third of flood damage over the past thirty years in the U.S. Increasing rainfall due to a warmer climate caused nearly $75 billion of the estimated $199 billion. This devastation occurred from 1988 to 2017.

The researchers published their research on Jan. 11, 2021 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The Goal of the Study on Flood Damage

This study helps settle an ongoing debate about the increasing financial burden of flood events due to climate change. It also sheds light on the total financial costs of global warming.

Lead author Frances Davenport, a Ph.D. student at Stanford’s School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences, said:

“The fact that extreme precipitation has been increasing and will likely increase in the future is well known. But what effect that has had on financial damages has been uncertain. Our analysis allows us to isolate how much of those changes in precipitation translate to changes in the cost of flooding, both now and in the future.”

The global insurance company Munich Re regards flood events as “the number-one natural peril in the U.S.” Flooding does rank among the top most common, ubiquitous, and expensive natural disasters.

The global insurance company Munich Re regards flood events as “the number-one natural peril in the U.S.” Flooding does rank among the top most common, ubiquitous, and expensive natural disasters.

However, until recently, scientists have been unsure if climate change contributes to flooding’s rising costs. And they wondered if so, how much. Researchers have been debating this topic for decades. We also saw this in the recent climate report from the U.S. government and the IPCC.

At the heart of the debate lies whether costly flood events stemmed from mainly socioeconomic factors. These include an increasing population, housing development, and rising property values. Much of the prior research mainly focused on detailed case studies about specific disasters or long-term changes in certain states. Some of the research also dealt with correlations between increasing rainfall and flood damages across the entire U.S.

How scientists proved that climate change is causing increasing flood damage

To prove their theory, the scientists began with higher resolution climate and socio-economic observations. Then, they applied advanced economic techniques to understand the correlation between historical rainfall variations and flooding costs. In addition to this, they employed statistics calculations and climate science to understand the relationship between intensifying precipitation and flooding costs.

Their in-depth analysis found that climate change has contributed significantly to the rising flood costs in the U.S. Furthermore, scientists believe that continued global warming will lead to more instances of these extreme flood events. Unless all countries in the United Nations Paris Agreement agree to lower emissions, flooding will likely only increase in severity and frequency.

“Previous studies have analyzed pieces of this puzzle, but this is the first study to combine rigorous economic analysis of the historical relationships between climate and flooding costs with really careful extreme event analyses in both historical observations and global climate models, across the whole United States,” said senior author and climate scientist Noah Diffenbaugh, the Kara J. Foundation Professor at Stanford Earth.

She added,

“By bringing all those pieces together, this framework provides a novel quantification not only of how much historical changes in precipitation have contributed to the costs of flooding but also how greenhouse gases influence the kinds of precipitation events that cause the most damaging flooding events.”

The scientists compare their analysis to other cause and effect scenarios. For example, they viewed how increasing the minimum wage will impact employment. Or how the addition or subtraction of a specific player contributes to the wins of a basketball team, for instance.

In their study, the research team developed an economic model based on observed precipitation and monthly instances of flood damage. Then, they controlled for other factors that might impact flood costs, such as rising home values. Next, they calculated the variation in intensifying precipitation over the 30 year study period. Finally, they calculated the economic cost if the fluctuations in precipitation hadn’t occurred.

“This counterfactual analysis is similar to computing how many games the Los Angeles Lakers would have won, with and without the addition of LeBron James, holding all other players constant,” said study co-author and economist Marshall Burke, an associate professor of Earth system science.

Implications of this study on the future of climate change research

After finalizing these calculations, the research team concluded that precipitation caused 36% of the flooding costs from 1988 to 2017. To reach this conclusion, they totaled the rainfall amounts across all individual states in the U.S. They also found that changes in precipitation resulted mostly from increases in extreme flood events. These have been responsible for the majority of flood expenses historically.

“What we find is that, even in states where the long-term mean precipitation hasn’t changed, in most cases, the wettest events have intensified, increasing the financial damages relative to what would have occurred without the changes in precipitation,” said Davenport, who received a Stanford Interdisciplinary Graduate Fellowship in 2020.

Final Thoughts: How understanding the threat of flood damage helps us in the future.

Final Thoughts: How understanding the threat of flood damage helps us in the future.

The research team notes their analysis of climate change’s financial costs could apply to other natural disasters.

“Accurately and comprehensively tallying the past and future costs of climate change is key to making good policy decisions,” said Burke. “This work shows that past climate change has already cost the U.S. economy billions of dollars, just due to flood damages alone.”

The team says their economic model could apply to other natural disasters in the U.S. and worldwide. It can also be used to understand climate impacts in various sectors of the economy. Finally, it could help with cost-benefit analyses of climate mitigation and adaptation strategies.

“That these results are as robust and definitive as they are really advances our understanding of the role of historical precipitation changes in the financial costs of flooding,” Diffenbaugh said.

“But, more broadly, the framework that we developed provides an objective basis for estimating what it will cost to adapt to continued climate change and the economic value of avoiding higher levels of global warming in the future.”